The 30th United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP30) – taking place 10-21 November 2025 in Belém, Brazil – brings together leaders, scientists, NGOs and activists from over 190 countries. Recognised as one of the world’s key events for climate change discussions and negotiations, COP30 serves as a unique platform to confront the unprecedented scale of the climate crisis with meaningful action. One of its main objectives is to strengthen collective commitment and determination toward emission reduction targets to limit global warming to 1.5°C, as outlined in the Paris Agreement

Blue Carbon and Geoengineering

Aligned with this major event, and recognising the growing interest in the ocean’s potential for carbon sequestration, a policy brief titled ‘Blue Carbon: Navigating Risks and Responsibilities in Geoengineering Solutions’ – prepared by the Tara Ocean Foundation (FTO) in collaboration with scientists from and within the framework of two Horizon Europe-funded projects: BIOcean5D and BlueRemediomics – has been prepared and will be presented during a dedicated webinar.

“Plankton are not only a cornerstone of marine food webs, they also play a vital role in the global carbon cycle,” explains André Abreu, head of international policy at FTO and co-leader of BIOcean5D’s work package dedicated to outreach, engagement and use of results. “When phytoplankton die, their biomass sinks to the ocean depths, carrying carbon with it and enabling the sequestration of significant amounts of CO2.”

Recognising this potential, several large-scale marine geoengineering approaches have been proposed to enhance this natural process. These include ocean fertilisation (adding nutrients to the ocean) and artificial upwelling (pumping nutrient-rich deep water to the surface), both designed to stimulate phytoplankton growth and increase CO2 absorption through photosynthesis. Other methods, such as ocean alkalinisation (adding alkaline minerals) and surface water cooling, aim to boost the ocean’s capacity to absorb CO2, while direct injection of captured CO2 into the deep ocean is being explored as a strategy for permanent carbon sequestration.

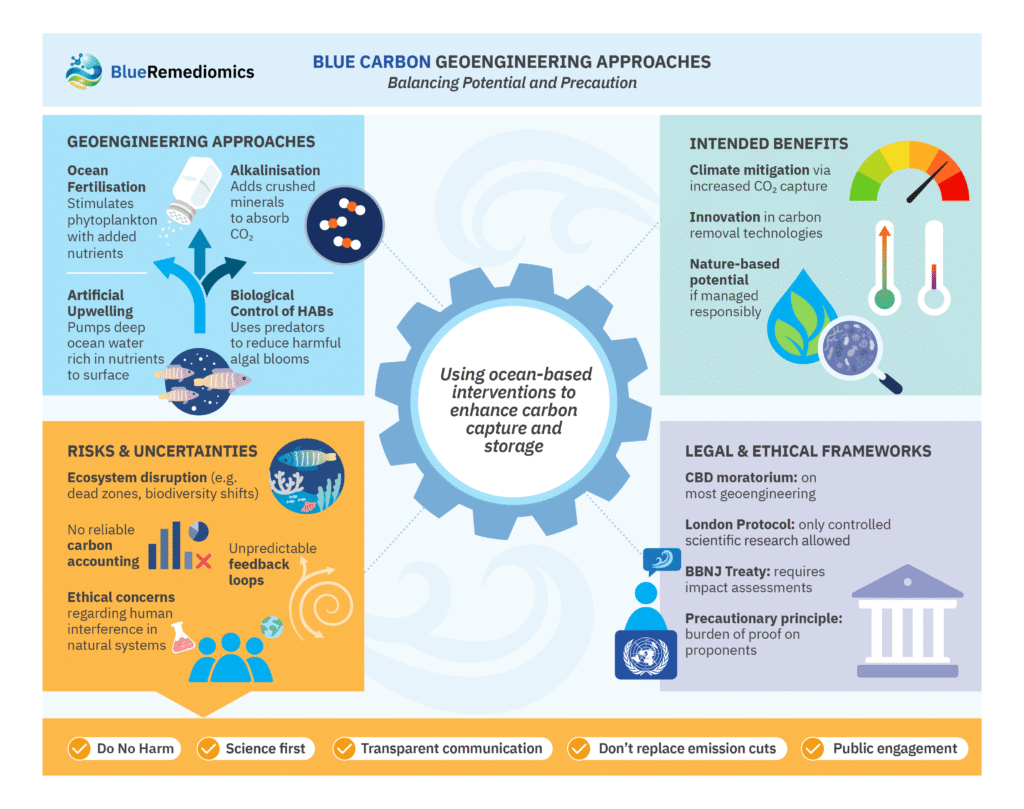

Figure 1 from the policy brief ‘Blue Carbon: Navigating Risks and Responsibilities in Geoengineering Solutions’, illustrating the potential benefits, associated risks and uncertainties, in addition to legal and ethical considerations of blue carbon sequestration, as outlined in the document. Credit: Tara Ocean Foundation and BlueRemediomics.

Figure 1 from the policy brief ‘Blue Carbon: Navigating Risks and Responsibilities in Geoengineering Solutions’, illustrating the potential benefits, associated risks and uncertainties, in addition to legal and ethical considerations of blue carbon sequestration, as outlined in the document. Credit: Tara Ocean Foundation and BlueRemediomics.

Risks and Uncertainties

While these strategies offer potential climate mitigation benefits, they also pose significant ecological risks. “Increased nutrient levels can disrupt the delicate balance of ocean habitats, leading to harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion, altered nutrient cycles and shifts in species composition, ultimately disturbing marine food webs,” explains Martin Alessandrini, Advocacy Officer at FTO. “Enhanced CO₂ uptake may further cause ocean acidification, as dissolved CO₂ forms carbonic acid, lowering seawater pH and altering marine chemistry with cascading effects on biodiversity – such as coral, shellfish and plankton – and ecosystem health.” Changes in species distribution and ecosystem structure could affect fish stocks, while increased organic matter sinking to the seafloor could impact deep-sea ecosystems. Overall, these interventions carry a risk of unintended consequences that could undermine their effectiveness and exacerbate existing environmental challenges.

Significant uncertainty remains regarding the scale and duration of these effects, as well as how the amount of carbon sequestered could be accurately quantified. Experiences from terrestrial carbon offset projects – such as reforestation, soil sequestration and direct capture – show that many have proved costly, environmentally problematic and unsustainable.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Ethical questions arise regarding the large-scale manipulation of natural ecosystems to offset the impacts of human activities. “Transparent and inclusive dialogue is essential to explore our relationship with nature, the boundaries of acceptable intervention and principles of intergenerational equity, environmental justice and the rights of nature,” explains André.

From a legal perspective, a moratorium on geoengineering activities that could affect biodiversity was adopted at the 2010 COP of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Similarly, in 2013, amendments to the London Convention and its Protocol prohibited any large-scale marine geoengineering not specifically approved. Moreover, the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, that recently reached the 60 ratifications required to trigger its entry in January 2026, mandates comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) for any activity potentially impacting marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdictions.

Recommendations and Priorities

Considering these risks, uncertainties and the complex interconnectedness of marine ecosystems, the policy brief emphasises a precautionary approach. “With current knowledge still limited, comprehensive research is needed to inform decision-making on ecological, socio-economic and ethical implications before pursuing any large-scale interventions. The brief therefore advocates maintaining or even strengthening the existing moratorium on marine carbon sequestration,” explains Martin.

Ultimately, significant emissions reductions remain essential to limit global temperature rise. “The priority must be to implement policies that reduce carbon emissions at their source before considering carbon sequestration to offset the remainder,” explains André. “Our responsibility – to current and future generations – is to protect marine ecosystems and biodiversity, and to safeguard the integrity, health and functioning of our ocean.”